Here is a list of the most common reasons that a builder or remodeler will fail inspection. Paying extra attention to them should make for fewer items that need correction.

- Missing Documentation

The most common reason a builder fails an inspection is the simplest (and least expensive) to remedy: not having all the required documents on-site.

- An engineer's foundation letter.

- The structural plans.

- The truss drawings.

- The plan for the HVAC ductwork and gas piping.

- The energy code documentations.

Of course, these documents will vary by jurisdiction, but it's up to the builder to know what they are and have them available.

- Improperly Placed Anchor Bolts

When you think about footings and foundations, you expect that the most significant error is improper rebar placement. You're mistaken.

Given the anchor-bolt requirements (these conform to the 2012 IRC), it's often easier to use epoxy anchors. J-bolts require coordination between framing and concrete crews.

The most significant error is surprising: missing or improperly placed foundation anchor bolts.

A common mistake is bolt locations that don't work with the mudsill joints. You need a bolt on each side of every joint on the sill. But many concrete guys just put bolts every 6 feet, rather than asking the framer where the joints will be. The problem could be avoided by better coordination between the framing crews and the concrete crews. Anchor bolts are a lot harder to fix than some other problems, so it's worth the effort to get them right the first time.

It's worth noting, too, that the 2015 IRC now requires the anchor bolts to be placed in the middle third of the width of a foundation plate. It complicates bolt placement even further. For a 2x4 plate, that means you've only got about 1 3/16 inches of tolerance to get it in the right spot.

- Braced Wall Errors

Code-mandated braced-wall requirements can be a head-scratcher for someone encountering them for the first time. The requirements are new to many builders, and a lot of them are still climbing the learning curve. But even when the bracing requirements are spelled out clearly on the plans, it's the little details that often escape framers. The most common oversight is missing blocking for braced wall panels. Code requires nailing along all panel edges, and that may require blocking between studs on tall walls or when boards are run horizontally. Fortunately, blocking is usually easy to add.

The other problem the building inspector sees most often—overdriven nails in bracing panels—can take a bit more work to correct. If you overdrive a nail, you can reduce the strength of a 7/16-inch panel to that of a 3/8-inch or 1/4-inch pane. It is a problem with nailing off hangers as well and overdriving nails dimples the steel, causing it to lose strength.

1. Weakened Joists and Beams

Inspectors see a lot of beams that aren't sized for the load or that lack proper bearing. It is more common in remodels than in new construction. It often comes up when a contractor cuts through an exterior wall to add a sliding door or removes an interior bearing wall to create a more open living space. If it's a load-bearing wall, they often think they can open it up and throw in a double 2x8. But you need to do a structural analysis to determine how much load the beam will need to support, especially if there are floors above. Newer homes have more complicated load paths. You need to pay attention before you start poking holes in the structure.

The gap at the end of this floor truss is a framing violation. Any truss or joist must have full bearing on the hanger seat. (photo: Jim Mattison)

One of the biggest problems is gaps at the ends of joists or trusses supported by hangers (photo at left). It doesn't take much: Gaps can be caused by a girder truss that's slightly crooked or out of plumb, making the time required to use a string line and level well spent.

Manufacturers of structural hangers usually specify a maximum gap of 1/8 inch between the end of the joist and the girder. Anything more significant will put the moment arm on the hanger and drastically reduce its load capacity. When hangers are double-shear nailed (toenailed), considerable gaps leave the nails completely missing the carried member.

5. Deck Ledgers and Braces

The culprits included too small hangers for the joists, improper fastening, and inadequate flashing that set the ledger up for rot.

Running diagonal braces in both directions for deck posts is an effective way to resist racking. (photo: Jim Findlay)

Despite more attention paid to decks, including the requirement in some jurisdictions for lateral connectors, some builders make lots of deck connection errors. On retrofits, we recommend that the contractor build a freestanding deck with the deck frame an inch or so away from the house and the structure independently supported on posts. It eliminates the difficulty of adequately flashing and fastening the ledger to the house.

Some builders make improper shear-bracing requirements on the deck. Typically, diagonal post bracing is required (photo at right ). To further resist racking, builders can also use flat-framed 2-bys run diagonally on the joists' underside. Racking is a source of failure over time. If the deck isn't properly braced, fasteners will work loose. Something as simple as kids running around and banging into rails can put stress on the pins.

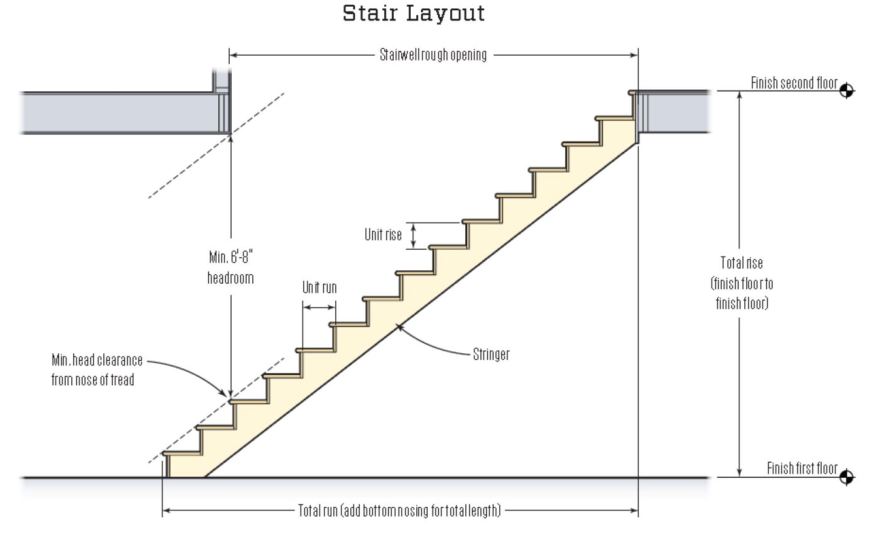

Stair Rise/Run Errors

Rise/run problems can arise where the builder doesn't have enough horizontal space for a planned stairway. Headroom is a limiting factor (see "Stair Layout" below). Many builders try to squeeze the stairs by simply pitching the stairway a little more steeply, resulting in a rise that may be too high or treads that are too narrow.

Another common problem is that builders, who may get the correct riser heights and tread depths, often don't adjust for the flooring's added thickness at the bottom. That leaves them with a bottom step that doesn't match the rest of the stairway.

Builders make many rise/run errors on stairs leading up to porches from sidewalks. Then they end up with a top or bottom riser that's too short. Some builders may assume that stair requirements need only interior stairs, but the riser and tread requirements apply equally to the interior and exterior.

If the stair isn't dimensioned correctly and someone falls, the jury will side against the contractor regardless of whether the stair caused the fall.

7. Stair Handrails and Guardrails

In some cases, stair handrails and guardrails are the wrong height as measured from the tread. They must be a minimum of 34 inches by code and no more than 38 inches high. In other cases, the connection to the stair isn’t secure enough.

Another common oversight is at the return at the top and bottom of a handrail. The rail can’t just end but has to die back into the wall or post or terminate the code calls a safety terminal. Otherwise, the railing end could catch things like pants pockets or purse straps, causing a fall. The terminal requirement is relatively new to residential construction but has long been a feature in commercial buildings, meant to protect firefighters in stairwells. There were cases where a firefighter was running up a stairway with a hose, and the hose got caught on the end of a handrail, pulling the firefighter down.

Fortunately, stair manufacturers now make various volutes and other termination pieces that make this requirement a lot easier to meet than in the past.

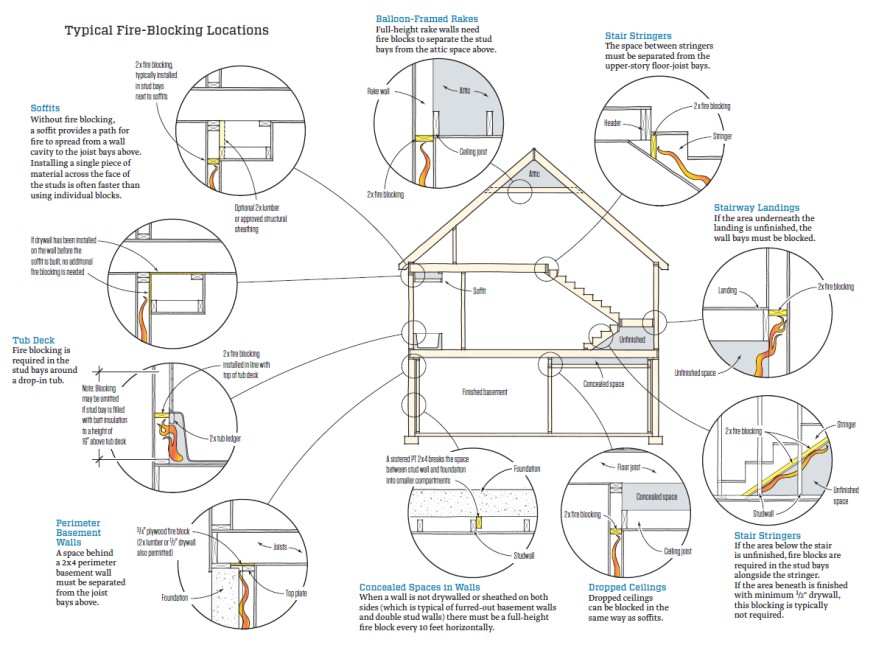

8. Missing or Inadequate Fire Blocking

Framers must install fire blocking at code-mandated locations in concealed cavities. The blocking prevents these cavities from acting as draft chimneys, thus slowing the spread of flame and smoke during a fire. It increases the time it takes to evacuate residents from the house.

Fire blocking must cut off the concealed draft openings between all vertical and horizontal cavities, essentially compartmentalizing each other's areas. And because they're often obscured by complex elements such as soffits, they're not always obvious, making it easy for the framer to miss spots that need to be blocked. But some builders who understand what areas need to be blocked often use the wrong materials. "One of the most common mistakes is not using the proper [fire-rated] caulking.

Often, a builder will use the suitable material but misuse it. For instance, some foam sealants are rated for use as fire blocking but can only be installed up to a maximum thickness, which they’re often not. Other builders try to get away with 7/16-inch OSB as fire blocking, rather than the 23/32 inch required by code. They usually have to add a second layer.

9. Air-Barrier Gaps

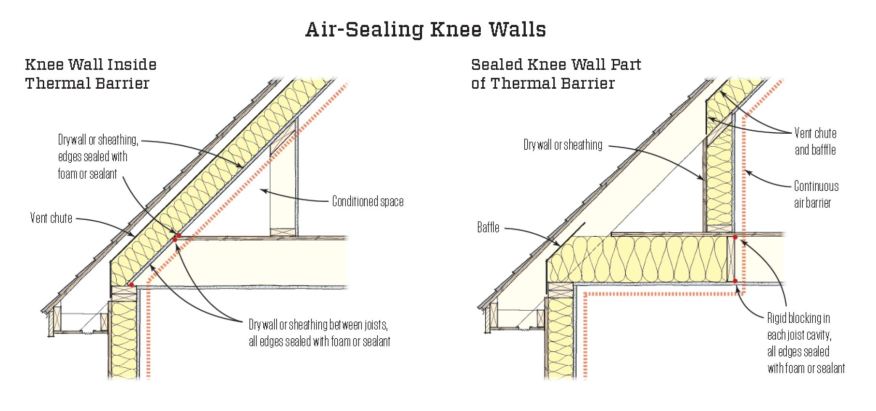

With more jurisdictions adopting energy codes, air-barrier gaps have become an issue. As is the case with fire blocking, these are often hidden spots, such as behind bump-outs for gas fireplaces. In the old days, the fireplace was just a hole in the wall. Now you have to wrap the thermal envelope around the back of it.

Many miss air barriers behind HVAC chases and attic knee walls. On a knee wall, this can be corrected by putting a rigid material like drywall, OSB, or Thermo-Ply on the back of the wall (see “Air-Sealing Knee Walls,” below), but a lot of framers aren’t doing it.

The best way to handle a knee wall area is to move the roofline's thermal barrier (left) and stand up the knee walls after the builder drywalled the ceiling. For production builders who may have less control in scheduling trade partners, the knee wall can serve as the thermal barrier (right), as long as the sheathing is installed on the backside. Also, note the blocking between floor joists. Without this critical framing addition, ventilation air from roof vents can flow freely through the floor cavity.

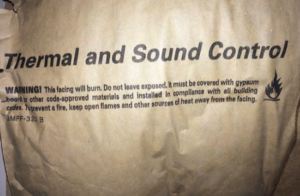

10. Exposed Kraft-Faced Insulation

When we speak about knee walls, the backing is more than an air barrier; it’s also needed to cover kraft-faced insulation batts. These are often left exposed in knee-wall areas and basements.

The warning label on paper-faced insulation batts clearly states: “This facing will burn ...” It cannot be left exposed but must be covered with drywall or another type of sheathing permitted by code. It applies in concealed framing cavities, in knee-wall areas (even if the knee-wall area is inaccessible), in attics, and crawlspaces. (photo: Glenn Mathewson)

Big mistake. You can’t leave the paper exposed. You can’t even leave a gap between it and the wall covering. The paper is coated with bituminous material and is highly flammable. You don’t want airflow over the surface that could feed a fire. The label printed on the insulation clearly states that the facing will burn and must contact the wall or ceiling covering.

That brings us back to the point we made at the beginning of this article: Builders could avoid many failed inspections if they read the manufacturers’ instructions and the documentation provided with the building permit. The time saved by not doing so can cost a lot more time later. It’s a lot easier to fix errors with a pencil than with a Sawzall or a sledgehammer.